The man who broke Sears now wants to fix it

What on Earth is Eddie Lampert thinking?

You'd think the average vulture capitalist, upon picking a company's carcass clean, would fly off. But not Eddie Lampert.

The hedge fund king's name is well known for the way he ran Sears into Chapter 11. But now that bankruptcy proceedings are underway, Lampert's trying to rescue the company from total liquidation. As of Wednesday, he was offering $5 billion to buy out the other creditors and keep about 425 stores open — along with around 50,000 jobs.

It may not work. Lampert's fighting with Sears' other creditors, who would mostly like to just sell off the company’s assets for spare parts and call it a day. The whole thing will likely be determined by an auction on Jan. 14, and then a court hearing scheduled for Jan. 31.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But the fact is, Lampert's offer is the only one that would keep Sears running in anything like its current form. Having destroyed the company, Lampert is now trying to rebuild it.

Just what on Earth is going on with this guy?

Perhaps Lampert is merely trying to squeeze a bit more blood from the stone. It's likely that very little if any of that $5 billion will come out of the hedge fund magnate's own pocket. The money will probably come from loans extended by some major banks. In other words: This could just be a rerun of the leveraged buyout strategy that gutted Sears in the first place.

Because of the weird way these operations work, Lampert and ESL Investments not only ran the company, they also served as one of its primary creditors. They made a ton of money off interest payments and fees. (That's largely why Lampert now has such a big role in the bankruptcy process he arguably drove Sears into — bankruptcy proceedings tend to prioritize selling off assets to make creditors as whole as possible.) While he was in charge, Lampert also had Sears sell off a lot of its brick-and-mortar properties to Seritage Growth Properties, a real estate company for which Lampert is the chairman. Sears went from owning its own shops to paying Lampert and company money to stay in them.

At the same time, Lampert's stock in the company — around a third of all its shares — is now pretty much worthless. In some ways, he's lost money on this deal, and in other ways he's made money. He's still worth about $1.1 billion, so he's doing fine, but he was worth over four times that in the early 2000s. Buying out Sears one more time may be an effort to add a bit more to the latter half of the ledger.

An even more cynical possibility is that Lampert is trying to protect himself from being sued over how he ran the company. "By reacquiring the company, he short-circuits any attempt by other potential suitors to get inside the Sears books and find out what kind of things may have actually been going on," Warren Shoulberg wrote at Forbes. "If he owns the place, they say, he won't sue himself, potentially saving himself billions in legal fees and judgments."

Shoulberg also wondered if there might be some arcane tax advantages for Lampert if he holds onto ownership of Sears and thus how its losses get tallied up for the IRS.

There's also the possibility, of course, that Lampert earnestly believes that everything he's done, mistaken or not, was done in Sears' best interests as a company. "I had a vision and a passion, but I never thought of myself as the only person who could save it," Lampert told The New York Times back in October. "I may have been the only person who tried to save it."

To an outsider, the idea that Lampert tried to save Sears seems positively through-the-looking-glass. Besides the vampiric financial arrangements Lampert imposed on the company — and the $6 billion in stock buybacks it spat out to shareholders under his guidance — Lampert's business acumen was less than stellar.

His attempts to revamp Sears for the internet commerce age hopped from one fad to the next, with poor results and little follow-through. He failed to properly invest in the company's physical infrastructure, resulting in stores that were rundown and uninviting. He siloed Sears' divisions off from one another and made them compete for resources — a strategy he imported from the financial world, apparently assuming it would work just as well in retail. But what may have fostered productive creativity in investment strategies turned out to be poisonous and dysfunctional on sales floors, where employees need to work together to help out customers. How could anyone view all this as an earnest effort to turn a business around?

But never underestimate the egos of Wall Street or their belief that finance capitalism is always and everywhere the best way to run the world. A telling tidbit in Lampert's case may be the 288-foot yacht he named "Fountainhead," after the novel by Ayn Rand that celebrates capitalists as Darwinian ubermenschen.

Lampert's investors may be jumping ship now. But back in the early 2000s, when he first took over Sears, Lampert was still widely viewed as a Wall Street wunderkind. "This guy pivoted from being a successful hedge fund manager to running a retail empire,” Mark Cohen, former CEO of Sears Canada, told the New York Post. "But he never viewed anyone's opinion but his own as valuable."

Earlier this month, Lampert's initial offer to buy Sears for $4.4 billion was rejected because it wouldn't cover the administrative expenses of the bankruptcy. Lampert responded by complaining about the millions in fees Sears' bankrutpcy advisors charged it to shepherd the company through the process — proof the man has neither self-awareness nor a sense of irony.

Lampert insisted to the Times that he never wanted to be CEO, but sort of fell into the role. "I wanted to be an idea generator," he said. "I was trying to be a catalyst, not the operating person." Now it seems Lampert wants to be the catalyst — or, dare we say, the fountainhead — one last time. Most people need to be the hero of their own stories, even the masters of the universe.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

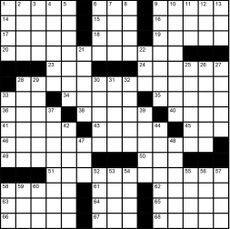

Magazine interactive crossword - April 26, 2024

Magazine interactive crossword - April 26, 2024Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - April 26, 2024

By The Week US Published

-

Magazine solutions - April 26, 2024

Magazine solutions - April 26, 2024Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - April 26, 2024

By The Week US Published

-

Magazine printables - April 26, 2024

Magazine printables - April 26, 2024Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - April 26, 2024

By The Week US Published